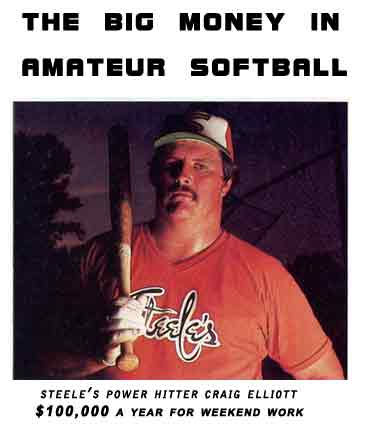

Craig Elliot stands at the plate, his eyes riveted on the pitcher, his back muscles rippling under his stretch nylon jersey in expectation. The pitcher lets fly a slow, looping pitch that sales maybe 20 feet in the air_Rip Sewell, the Pittsburgh Pirates right-hander of an earlier day, called such junk his “Eephus” pitch before it descends toward the plate. Elliott uncoils and, in a marvel of timing, puts all of his 280 pounds into a swing that would have impressed the Mighty Casey himself. The noise of the bat meeting the ball sounds like a sadistic fraternity hazer's paddle meeting a pledges behind. The ball sales over the deepest part of the centerfield fence, a distance of 315 feet, and Elliott smiles as he trots around the bases to the crowd's cheers. Craig Elliot stands at the plate, his eyes riveted on the pitcher, his back muscles rippling under his stretch nylon jersey in expectation. The pitcher lets fly a slow, looping pitch that sales maybe 20 feet in the air_Rip Sewell, the Pittsburgh Pirates right-hander of an earlier day, called such junk his “Eephus” pitch before it descends toward the plate. Elliott uncoils and, in a marvel of timing, puts all of his 280 pounds into a swing that would have impressed the Mighty Casey himself. The noise of the bat meeting the ball sounds like a sadistic fraternity hazer's paddle meeting a pledges behind. The ball sales over the deepest part of the centerfield fence, a distance of 315 feet, and Elliott smiles as he trots around the bases to the crowd's cheers.

You would smile, to, if you were paid an estimated $100,000 a year for weekend work as an amateur playing a game even little boys can handle. Elliott, 33, spends the better part of each week in and around Wadley, Alabama, up north of Montgomery, working as a paving contractor. But on weekends he dons the uniform of the Grafton, Ohio Steele's and plays about 180 softball games a year. In 1983 Elliott hit a phenomenal 392 home runs for another team, the Gordon, Georgia team called Elite. This year he has already passed 200 home runs, with half the season still to come.

Steele's Sports Company, a manufacturer of softball and baseball equipment, spends about $400,000 on personal appearance contracts and transportation costs flies players from Florida, Kentucky, Alabama and Wisconsin to games as far away as Hawaii.. According to Dennis Helmig, Steele's Pres., that’s just the price you pay to stay competitive in the softball business. Our sales have doubled year to year since we’ve had the team, he says. This is a big business.

Well, there is big and there is big. You won’t find softball in one of Martin Feldstein’s or Larry Klein's econo-metric models or on Wassily Leontiel's input-output charts. But for thousands of small towns and dozen of big cities around the country, amateur fast pitch and slow pitch softball is a potent force in the economy of summer. Revenues generated by the game are growing at a steady 6% a year. In direct measure, the value of equipment sales plus the money put into private softball complexes easily surpasses 500 million annually.

How does that work out? Like this:

Bats. The major manufacturers, the largest are Hillerich & Bradsby, which makes the famed Louisville Slugger; Easton Aluminum, whose aluminum bats are considered the best in the business, and Ten-Pro, sell about 230,000 dozen bats annually, worth 57 million at retail.

Balls. Serious softball consumes balls at a ferocious rate, about 1 million dozen annually, worth about $65 million at retail. There is a lot of profit in softballs. Most of them are stitched in Haiti, where the labor cost is one dollar per dozen, and retailed for around $60 a dozen. There is no “official” softball as local tastes very. In New York City the premier ball is the Clincher, a 12 inch circumference ball made by Albany, New York based J. DeBeer & Son, Inc. DeBeer supplies a 16 inch circumference version to Chicago, where softball is played barehanded. Worth Sports Company in Tullahoma, Tennessee, the largest softball manufacturer, also varies the size and composition of the ball depending on where it is shipped.

Gloves. This is $100 million retail business, dominated by Rawlings Sporting Goods and Wilson Sporting Goods. Like their baseball counterparts, softball gloves have been creeping up in size. Some now spanned 13.5 inches, against a standard only five years ago of 12 inches. Rawlings and Wilson, while still dominating the international glove market, have been pushed aside at the high-end by what Martin Archer, sales manager for Hillarich and Bradsby's athletic goods division, admits is the higher quality of Japanese gloves.

Uniforms. The major uniform maker is Russell Corporation in Alexander City, Alabama. According to William Hardy, senior vice president, softball uniforms are a $225 million a year business. Richard Spanjian, whose Marcos, California firm also makes uniforms, thinks the market is even bigger. Take a market like Yuma Arizona he says there are 42,000 people in the middle of nowhere 130 teams. In San Diego, where we are strong, there are probably 1500 teams. With an average retail uniform cost of $30 per player it’s just got to be bigger than Russell says.

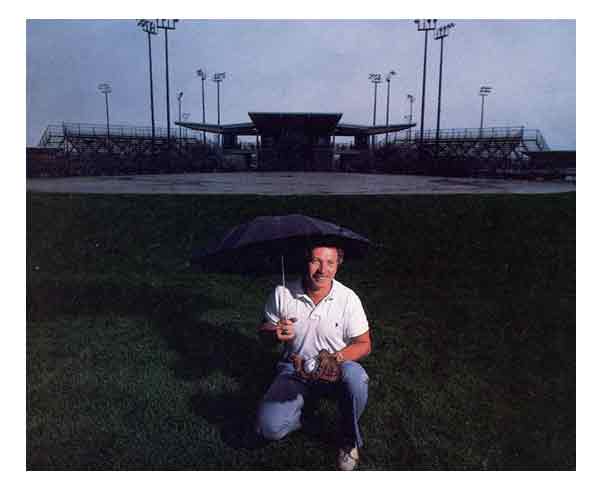

Shoes. Softball cleats are fatter than baseball spikes. The dominant makers are such athletic shoe giant as Coverse in Wilmington, Massachusetts and PUMA USA in Farmingham, Massachusetts. The total market is about $15 million. To help against the multiplier effect, consider Hutcheson Kansas a city of 40,000. In addition to the 30 or so softball diamonds the city maintains out of its recreation budget, there is also a separately budgeted seven diamond complex that cost the city more than $200,000 a year to keep in shape. Why? Says James’s Swint, who runs the complex for the city and who is also executive director of theSoftball Owbers and Directors Association. (SODA) There have been numerous studies done by the city on the impact of tournament softball. For the money they spend on this complex, the town gets back about 1.5 million every year in revenues from outsiders that’s money they spend in restaurants and hotels that wouldn’t come into the town otherwise.

It’s that way all over America according to the Amateur Softball Association something like 23 million people played organized softball on over 100,000 diamonds around the country. That’s softball in which the best teams from local leagues go into tournament series leading to any of 33 national championships or even four world championships. It doesn’t include an additional 17 million people who play and recreation leagues or just spend a summer night planned for the sheer fun of it, with the pitcher or two of beer and a pizza afterwards and maybe a videotape replay.

If Hutchinson’s multiplier is in any way indicative of organized softballs effect on local economies, it’s easy to see why teams like the Steele's Sports Company spent so much on personnel, top pictures reportedly command $40,000 or more per season, and why top fast pitch teams go as far as New Zealand to import talent.

The multiplier also explains why private softball complexes are springing up all over the country. Entrepreneurs hopeful of tapping a new market are rushing in to relieve strapped municipalities of a significant item in their recreation budgets by running softball fields as a business.

About 70 complexes have opened around the country, according to Swint. Each consist of 4 to 12 fields, lights for nighttime play, clubhouse and concession facilities and lots of stands for the fans. Each complex cost in the neighborhood of $750,000 to 2 million, says Swint and that doesn’t include the cost of the land. They're high overhead operations, what would the cost of lighting and maintenance, but people keep opening them. You can make money, though, if you can bring in enough teams and other events. While a city such as Houston has trouble filling six private softball complexes, and other cities, such as Dallas, can’t get enough of them. Right now, Swint points out, there are only two complexes in Metropolitan Dallas for several thousand teams.

Softballs growing popularity means of course, that it will evolve in order to widen its participation. That’s what explains the slow but steady demise of fast pitch, once the dominant game, and the concurrent rise a slow pitch softball, which is more often coed and played on a recreational as well as a tournament level.

The growing popularity of softball is also tempting people to tamper with the equipment. For example, Bill Merritt, a New York City architect turn sporting-goods entrepreneur, has redesigned the bat away from its traditional tapered cylindrical shape and towards a kind of rounded triangle. The bats, dubbed Broadsiders, allow slow pitch hitters to get more wood on the ball, which means more hits and more runs, which players seem to like. Knowing what its members want, the Amateur Softball Association barely hesitated before sanctioning merits bat at its annual meeting last winter. That could translate into some hefty lumber four Merritt's who has already sold more than 10,000 bats at a retail price of $25 each for wood and $55 for aluminum.

One other factor belongs in this reckoning the prize money anted in what the ASA calls bandit tournaments. They exist in abundance. Syracuse, New York alone runs about six bandit tournaments a weekend during the summer, and you find them all over upstate New York and the North country, says William Plummer, communications director of the ASA. In a typical bandit tournament, 15 to 20 teams will put up $125-$250 each. The total prize pool will run around $5000, with the winning team receiving $1000.

Whereever you get these kinds of games, says Plummer, there aren't any restrictions on rosters. A few teams load up on big players and feast on the other teams. How fair is that? But nobody other than the ASA seems to mind.

It's considerable size outside, softball has a potent symbolic role in economic affairs. Japan is the world's second-biggest softball market, and presumably ripe for American made aluminum bats, which are considered the best in the world. They are so good, in fact, that Japan which seems to make so many other things so well has had no success in the US despite an open market. But the US sells only 500 aluminum bats a year in Japan out of a potential 67,000 dozen, which is the size of Japan's bat market. Why? The Japanese say that American bats don't fit their needs. But David Lumley, a spokesman for Wilson says otherwise. If ever there was an example of tariff barriers, this is it. The Cubans, who are among the best ballplayers in the world, buy bats in the US. How can they not be good enough for the Japanese? How indeed? |