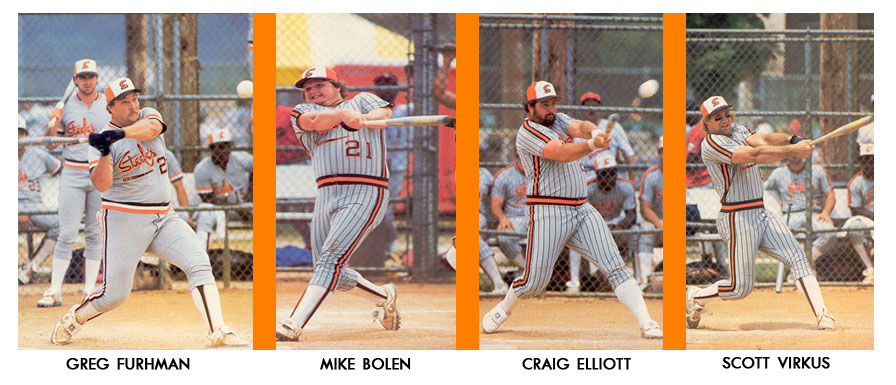

It's an odd thing, but at the No. 1 diamond at the Flora Park,softball complex in Opelika, Ala, the crowd standing beyond the outfield fence is much bigger than the one sitting behind home plate and along the foul lines. There are Little Leaguers in gaudy uniforms out there, picnicking families, young lovers, college and high school kids. And almost all of them are carrying gloves. There's a good reason for that: The Steele's Sports Company slo-pitch softball team is in town, and when those guys play, more balls are caught outside the park than in it. Indeed, Steele's is a team that makes the '27 Yankees look like a bunch of Punch and Judy hitters.

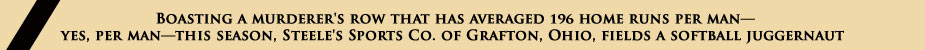

Watch out, you people over the fence, Greg (Bull) Fuhrman is at the plate, all 300-plus pounds of him, waving that aluminum Steele's bat as if it were a ballpoint pen. The pitch comes floating into the strike zone. Fuhrman lifts one elephantine leg Mel Ott style, and as bat meets ball there comes from him a sound like none you have ever heard before, a sound deeper than a weightlifter's grunt, louder than a bellow. A charging lion would stop in his tracks at the sound of Bull's roar. The noise carries well beyond the ballpark. So does the ball. So, for that matter, do most of the balls hit by the menacing sluggers on what is, in softball circles, rapidly becoming known as "the greatest team of all time."

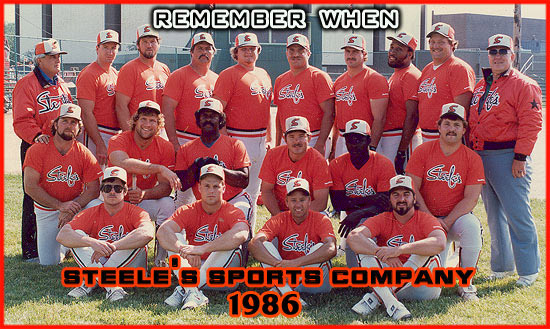

Could be. Steele's stats are certainly mind-boggling, a towering monument to wretched excess. With about two-thirds of their 235-or-so-game 1986 season played, Steele's has a record of 147-8. The team has averaged 34 runs a game, with 17 homers. Five of its regulars are hitting over .700, and all of the remaining 12 players are over .610. The team batting average is a cool .680 with—get this—2,622 homers. In that doubleheader in Opelika against the best players that could be mustered from the surrounding countryside, Steele's outscored its opponents 128-34. Only a few weeks earlier, Steele's scored a record 91 runs against Shubin's of Los Angeles—that's 91 runs in one game. And in a seven-game blitzkrieg of Colorado shortly afterward, the team won by scores of 42-10, 66-24, 54-6, 60-4, 49-5, 52-9 and 65-9.

Last year, Steele's won the Amateur Softball Association Super (highest) Division National Championship. This year, with a much better team, its goal is Softball's triple crown—the ASA, the United States Slo-Pitch Softball Association (USSSA) and the Independent Softball Association (ISA) tournament titles. The talent is certainly there. Steele's has, for example, 33-year-old Craig Elliott, another 300-pounder who in 1983 set a national single-season softball home run record (since, incredibly, broken) of 390. He has won Most Valuable Player awards in five different national tournaments and has played on four championship teams. An independently wealthy paving contractor in Wadley, Ala, Elliott will, nonetheless, earn nearly $100,000 this year for allowing Steele's to use his name on one of the company's bats. Not every Steele's player is so well paid, but most, either by working for the company directly or with "personal services" contracts, make five-figure salaries for playing the same game the rest of us play over a few beers on weekends.

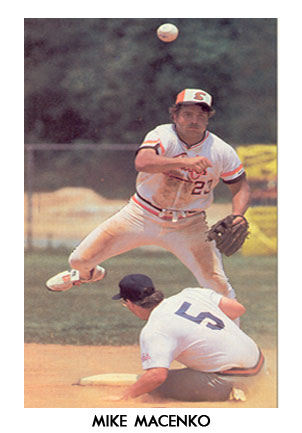

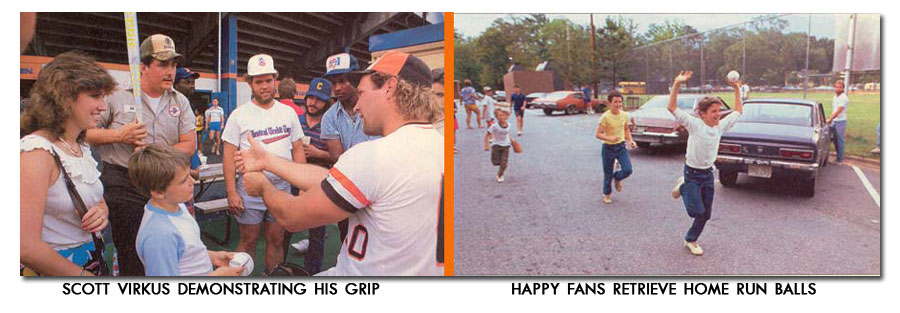

Elliott is big in every way in softball circles, but so are 265-pound first baseman Mike Bolen, 245-pound second baseman Mike Macenko, Fuhrman and Mighty Joe Young, a 235-pound former Grambling linebacker who sells shoes out of the trunk of his car and, at 38, is something of a softball legend. There are also such up-and-coming greats as Doug Roberson, a fence-climbing 220-pound left-fielder, and Scott Virkus, a 6'6", 295-pound right-fielder who looks like a gigantic Gary Carter. Virkus hit 150 homers in 81 games before leaving the team July 14 to try out as a defensive end with the Buffalo Bills. Alas, Virkus failed his physical and is hoping another NFL team will call.

Four other Steele's players weigh more than 230 pounds. Only Greg Whitlock, the shortstop, is under 200, and he goes 190. The average weight is 244, the average height 6'3", the average age 30. And, oh my, can they hit that big, fat (12-inch circumference) ball. Most softball parks have fences some 275 to 300 feet from home plate, distances that tax the best players and are generally beyond the power of weekenders. The Steele's stars might as well be playing in their own living rooms as in one of these bandboxes.

In the two games they played in the Opelika park, where the fences are 285 feet all the way around, they hit 80 homers. Playing in Columbus, Ga., the day before on a regulation high school baseball diamond with 340-foot power alleys, they hit 14 homers. Two by Virkus cleared a school building across the street from the leftfield fence, one by third baseman Charles Wright, who currently leads the club with 315 homers, shattered a window in that same building, and another by Macenko landed in the top branches of a pine tree beyond the fence in right center. All four homers were hit between 375 and 400 feet, Virkus's maybe farther. Remember, it's a softball they're hitting, and one pitched so slowly that all the power must come from the batter. Steele's is not in the least intimidated by baseball parks. The guys have hit balls over the fences in every park they have ever played in, including Denver's Mile High Stadium.

The Steele's Sports Company headquarters are in Grafton, Ohio, but the softball players, who promote the firm's products by demonstrating what remarkable uses they can be put to, barnstorm hither and yon, knocking off teams from Opelika toLas Vegas. And they don't just play bumpkins. They enter virtually every major tournament, from the Azalea Festival in Wilmington, N.C., to the Coca-Cola Classic in Maryville. The company was founded in 1979 by a former softball player, Dennis Helmig, who transformed an auto parts business into one of the country's fastest-growing sports equipment manufacturing firms, turning out primarily baseball and softball gear. Steele's is not yet in the same bat, ball and glove league with such major outfits as Worth Sports or Dudley Sports, but it's gaining on them, more than doubling its total revenues in the last year from $2.2 million to $4.5 million. The projected figure for 1986 is $8 million. Softball is big business these days. More than 40 million Americans play it, and upwards of $500 million is spent annually on equipment and playing fields. Helmig's amazing team, organized only six years ago, is his company's living, breathing, slugging advertisement. Use one of our bats, his players imply, and you, too, can hit 400-foot home runs. That's nonsense, of course. Indeed, the game Steele's plays is hardly soft-ball as we know it.

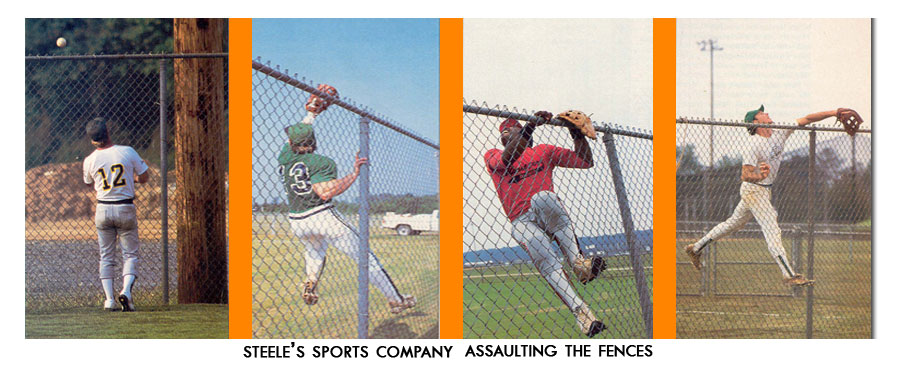

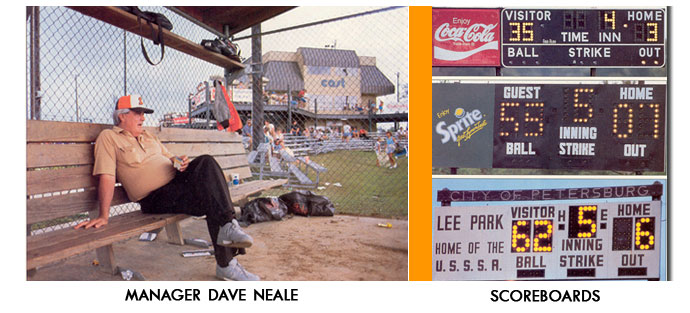

The Steele's convoy—two brown-and-orange vans with sides boldly painted NATIONAL CHAMPIONS, and two rented cars—motors through the lush, thickly forested Georgia countryside. The vans will do close to 100,000 miles apiece this season, mainly because manager Dave Neale is flat-out terrified of airplanes. Husky and silver-haired, Neale is an old sandlot baseball and softball player from Cleveland.

"We'd play money games in my neighborhood, winner take the pot," he recalls. "Many's the day I'd take the last $20 in the house to get in a game." Neale, 48, has been in softball for 31 years, many of them managing a team representing the bar he once owned in Cleveland, the Hillcrest Tavern; for the last four years he has managed Steele's. He has been married to Arlene for 30 years. She always sits beside him in the van, working on her needlepoint or watching soaps on her miniature battery-powered television set. She is a cheerful, attractive blonde who waits patiently through the incalculable boredom of Steele's lopsided, home run-saturated ball games.

Neale, who takes his softball as seriously as Gene Mauch takes his baseball, sometimes refers to himself wearily as a "glorified babysitter." On this very tour he was obliged to order one player, a 34-year-old, home after an infantile dispute over who would sit where in one of the vans. In three decades, Neale has seen and heard it all. Once, when he was managing a team called the Cleveland Competitors (then the property of former Cleveland Cavalier owner Ted Stepien), he instructed his players to assemble at 7 a.m. to catch a bus for a game in Fort Wayne, Ind. One player, Freddie Miller, "the strangest human being they ever invented," was still missing at 7:05, so Neale, a fanatic on punctuality, commanded the bus to leave. Miller arrived for the game in the third inning, looking harried and apologetic. Neale gave him the cold shoulder. "You and me are history," he advised the latecomer. But Miller begged him for a chance to explain. Neale finally relented, and he's eternally grateful he did, for he firmly believes that Miller's explanation, even though it was probably fiction, belongs in the Alibi Hall of Fame. It seems Miller had taken up with another man's wife, and on the night before the game the cuckold caught the two of them in flagrante delicto. The aggrieved husband drew a pistol and pointed it at Miller. And he kept it pointed at him, said Miller, right up to the time the team bus was scheduled to leave. Finally, a half hour after the bus had departed, his captor drifted off to sleep, and Miller was able to escape with his life. Now, after all that, couldn't he play? Neale shrugged. Neale, who takes his softball as seriously as Gene Mauch takes his baseball, sometimes refers to himself wearily as a "glorified babysitter." On this very tour he was obliged to order one player, a 34-year-old, home after an infantile dispute over who would sit where in one of the vans. In three decades, Neale has seen and heard it all. Once, when he was managing a team called the Cleveland Competitors (then the property of former Cleveland Cavalier owner Ted Stepien), he instructed his players to assemble at 7 a.m. to catch a bus for a game in Fort Wayne, Ind. One player, Freddie Miller, "the strangest human being they ever invented," was still missing at 7:05, so Neale, a fanatic on punctuality, commanded the bus to leave. Miller arrived for the game in the third inning, looking harried and apologetic. Neale gave him the cold shoulder. "You and me are history," he advised the latecomer. But Miller begged him for a chance to explain. Neale finally relented, and he's eternally grateful he did, for he firmly believes that Miller's explanation, even though it was probably fiction, belongs in the Alibi Hall of Fame. It seems Miller had taken up with another man's wife, and on the night before the game the cuckold caught the two of them in flagrante delicto. The aggrieved husband drew a pistol and pointed it at Miller. And he kept it pointed at him, said Miller, right up to the time the team bus was scheduled to leave. Finally, a half hour after the bus had departed, his captor drifted off to sleep, and Miller was able to escape with his life. Now, after all that, couldn't he play? Neale shrugged.

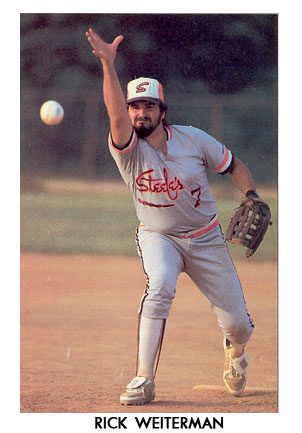

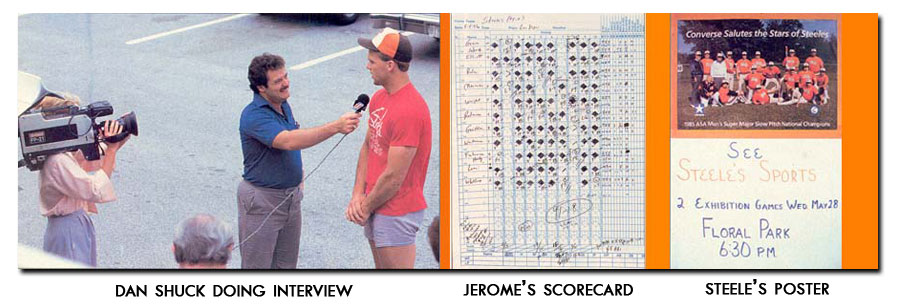

Jerome Ernest, 44, is the team's traveling secretary, statistician, demon publicist and van driver. He is a short, plump, bespectacled man who appears positively dwarfish alongside the mastodons whose exploits he so faithfully records. He is easily the most trusted man in this extraordinary troupe, the one person capable of locating the remote ballparks in the obscure towns the team barnstorms. "Ask Jerome" is everyone's answer to sticky questions of fact or geography. Everyone knows the importance of being Ernest. Ernest is the man sportswriters seek out for the latest Steele's statistical marvels. He reels them off from memory. When his players hit 21 home runs in the fourth inning of the first game of the doubleheader against the two all-star teams from Opelika, Ernest was on hand to put the achievement in historical perspective. "The inning record [in organized softball] is 27," he told a local reporter. "Fifty-two is the record for a game. Twice this year we've hit 46 in a game, and one other time we hit 45. [Since then, Steele's has had 48-and 47-home run games.] And those were all five-inning games." When Steele's pitcher Rick Weiterman got his 21st straight hit, Ernest was at the ready. "Roberson also had 21 hits in a row this year, and that included 9 home runs in a row. In four games in Denver, he had 17 homers and 44 RBIs. Bolen had 18 straight hits, made an out and then had 9 more—that's 27 for 28. And Joe Young had 15 straight and 24 for 25."

Steele's home runs are hit with such numbing frequency that Ernest has taken to grading them. If a ball is merely knocked out of the park, he just darkens in the space in his scorecard. If it is hit farther than the average, he puts a line underneath the home run mark. A three-line homer is Mickey Mantle country. Virkus got a pair of three-liners for his two over-the-roof shots in Columbus, Ga., and another for one he hit in Opelika that cleared the leftfield fence at 285 feet, soared over two rows of parked cars and bounced against a second fence bordering the parking lot. Ernest had a local recreation department official put a tape measure to that one. It came to 410 feet, a fact duly recorded in Ernest's scorebook. When Elliott hit one almost as far in the same game, he hurried over to Ernest to check on his grade. It was only a two-liner, and the big slugger returned to the bench looking as downcast as the class grind who has gotten a B+ in an exam he thought he had wired. But Elliott raised no protest. Ernest's scorecard is the law. Steele's home runs are hit with such numbing frequency that Ernest has taken to grading them. If a ball is merely knocked out of the park, he just darkens in the space in his scorecard. If it is hit farther than the average, he puts a line underneath the home run mark. A three-line homer is Mickey Mantle country. Virkus got a pair of three-liners for his two over-the-roof shots in Columbus, Ga., and another for one he hit in Opelika that cleared the leftfield fence at 285 feet, soared over two rows of parked cars and bounced against a second fence bordering the parking lot. Ernest had a local recreation department official put a tape measure to that one. It came to 410 feet, a fact duly recorded in Ernest's scorebook. When Elliott hit one almost as far in the same game, he hurried over to Ernest to check on his grade. It was only a two-liner, and the big slugger returned to the bench looking as downcast as the class grind who has gotten a B+ in an exam he thought he had wired. But Elliott raised no protest. Ernest's scorecard is the law.

It's a wonder, of course, that the man is able to keep track of what's going on out there. When a team scores 91 runs in a game, a statistician's scorecard can look like the Rosetta stone. "You can't look away for a second," says Ernest of the unnatural concentration his job requires, "or you'll miss something. They go through that batting order so fast."

In the smaller communities where soft-ball is the reigning summertime activity, the arrival of the Steele's team becomes a matter of civic pride. The players, dressed in one of their four tasteful uniforms, are deferred to as if they were royalty. It matters not at all to the men of Steele's that most American sports fans haven't the foggiest idea who they are or what they do; in their own little world they are hot stuff. Ernest and Neale set up the back-breaking schedule in advance, but they'll deviate from it on occasion to oblige a Steele's client. This spring, for example, they went well out of their way to play a game in Dothan, Ala., at the request of the town's parks and recreation department. "They really did a nice job of promoting," says Neale. "The mayor was there and a lot of people showed up. Three stores picked up Steele's sporting goods, so I don't think of that as having gone 12 hours out of our way."

The team's arrival is generally preceded by radio and TV announcements and by advertisements placed in the local papers. Ernest sees to it that game details are relayed quickly to sports desks and newsrooms, NATIONAL POWER ROUTS Columbus ALL-STARS read the headline over an account in the Columbus, Ga., Ledger on May 28, after the team had whipped the locals by the comparatively modest score of 27-10. "Steele's, considered the nation's best softball team, with both a 79-5 record and a record 91 home runs [sic] in one recent game, hit 14 homers Tuesday night. The All-Stars hit two: Jimmy Ennis had both."

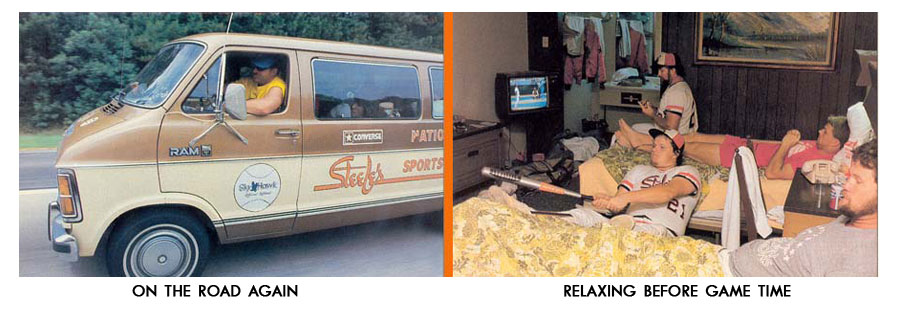

Outfielder Dan Griffin, at 230 pounds, is the smallest stud-poker player in room 226 of the Day's Inn in Savannah, Ga. Virkus rocks back and forth in a suddenly fragile-looking chair, stretching balloon arms behind his curly head. Fuhrman takes up most of the double bed, which also serves as the card table. Fuhrman is the team's champion eater, a title Neale would prefer he relinquish. "He's got this thing about showing everybody how much he can eat," says Neale. "And we're talking big-time eating here. I'd put him up against anybody. We ate at a place in Denton, Texas, last season. They had a deal where if you could finish a 72-ounce steak in less than an hour, you didn't have to pay for it. Well, the first night, Bull finishes it in 40 minutes. The second night he's down to 35 minutes. They told him not to come back." Henry (Hankster) McBeth, 6'5", 285, sits crouched over his cards, tapping them on the edge of the bed. The 265-pound Bolen kneels childlike at the foot of the bed, his oddly high-pitched voice urging haste since it's now past five o'clock and the vans are to depart at 5:30.

A Leave It To Beaver rerun is playing unwatched on the television set. Outside, the skies, which were sunny only an hour earlier, are black and forbidding. There is a crackle of lightning, thunder and finally the inevitable rain—sheets of it, falling with waterfall force. Virkus gazes lazily out the window and mutters, "This crap has been following us." Another lightning explosion is accompanied by shouts of protest from the cardplayers. "No way we play tonight," says Griffin, dealing. Neale, ever conscious of the time, steps into the room. "You guys know what time it is?" he inquires mildly. "No," says Bolen. "Five-ten," says Neale. "That gives us 20 more minutes of cards," says Fuhrman. "Right," says Neale, "but be in the vans at 5:30." "We gonna play?" asks Virkus. "We're gonna try," says Neale, backing out the door.

Virkus counts his winnings in his own room. He is watched by his 20-year-old wife, Antoinette, who sits prettily on the bed wearing a polka-dot dress. Except for Arlene Neale, Antoinette is the only wife on the tour, and she has the look of a lost child. She had wandered into the card game several times, only to retreat in confusion as the big men ignored her. "Did you win?" she asks her husband. "Only about 60 bucks," he says proudly. "Oh, then I'm going shopping right away." She ruffles her skirt around knees turned pink from the early afternoon sun. Virkus removes his T-shirt and tennis shorts and stands there in his blue bikini undershorts. He is a figure of Schwarzeneggerian definition, only much bigger.

"For me softball started out as fun," he says, slipping into the orange jersey Steele's will wear this rainy night in Georgia."It was something the guys did on Sunday in my town, Rochester, New York,after being out Saturday nights. Everybody had hangovers. Then it started getting real serious. Pretty soon we had a good B club. But I always had football. I went out to City College of San Francisco—my grandmother lives out there—and that's where I developed my speed." Antoinette helps him pull down his jersey. "I can do a 4.6 forty, you know. Well, they had me playing tight end, and I'd work out running up and down those hills they got there. I just got faster. I could see myself evolving. I'd had one year at Purdue. Played tight end, trading time with a five-year man. We dumped Georgia Tech in the Peach Bowl that year." Antoinette sits down again, smoothing her dress. "But I didn't have the grades in college. I just couldn't get interested in it. So I dropped out and played some semipro football in Rochester, and I did really good—scored 19 touchdowns in only seven games. The Buffalo Bills got interested and gave me the opportunity. They moved me to defensive end. I made the club, but those first two years were like a freshman and sophomore year in college for me. Fundamentally, I was way behind. They let me go, and I went to Indianapolis. Led the team in sacks last year with six, and then they let me go."

Virkus is in full uniform now. He fixes his orange, brown and white cap and pounds an immense fist into his softball glove. "Neale heard about me in soft-ball—they get a lot of information by word of mouth. So he contacted me. When I got released by the Colts, I decided to give this a go. It's nice to play in this kind of situation. There's no pressure on me to perform, so I go up there with a relaxed attitude. Oh, I still get upset. The pitchers try to take you out of the game, like that Buddy Slater of Houston's Smythe Sox. He did so much talking that I wanted to hit the ball right back at him instead of out of the park. You see, when he does that, he's accomplished his purpose. He's got me thinking about him, not the ball. Bull helps me." He looks hopeful. "Bull also helps me learn about sales. If I can catch on with Steele's in the upstate New York area, I'll have something after football. And I like softball. You see me, you see I run out everything. I want to get as much exercise out of this as possible. Hell, if you hit home runs all the time, you finish a game without even breaking a sweat."

Griffin says he's fascinated with guys like Bolen. Griff is half-dozing in the back seat of the rental car that trails the vans across Georgia. "The best hitter on this team is Mike Bolen," he says. "He always hits the ball on the fat part of the bat. He always hits it sharp. He has that concentration. When we get 50 runs ahead, I check out the girls in the stands, talk to the people around the outfield fence. Not Mike. I wonder what some of these guys will do when they can't play anymore. It's a funny game, you know. People who know about it know who does what when. When we get in the thick of it, in a big tournament, you find out who's got the stuff. Mike has. Now he's after that record—.769 for a season. Mike Nye set it in Jacksonville 10 years ago. He was a leadoff hitter, basically a hole hitter. He was a pit bull. He's about 40 now, but still playing. Mike's going for his record, and the funny thing is he got off to a slow start. So what's he hitting now—.768 or something? [Bolen has since slumped to .753.] The guy just loves softball. His idols back in Tennessee were softball players, particularly a guy named Stan Harvey. Plays for Howard's/Western Steer [in Denver, N.C.] now. Isn't that something, having a softball player as your idol? Hell, I wasn't even thinking about softball when I was growing up in Detroit. Mike is something else."

Neale thinks Bolen is "the most underrated hitter in the United States. He's so disciplined. Works for us, you know, as a salesman. And he'll give hitting demonstrations. Our sales in Tennessee are up 200 percent since he joined us."

Earlier in the day, Bolen was having lunch and talking softball in a place called The Filling Station in Savannah. He is a huge man, 31 years old, who incongruously has a wispy strawberry blond goatee. It makes him look like a Mennonite, or maybe Burl Ives. He has a soft, melodious voice, a folk singer's voice. On the field he is the most imperious of the Steele's players, an almost haughty figure, unsmiling and uncompromising. Off the field he is pleasant and accommodating. "I can't think about hitting .769," Bolen says. "That's awesome. We're a home run-oriented team, and all I think about is hitting the ball hard, staying in a groove. When the other team gets knocked out of it in the first inning, you just have to force yourself to concentrate. I work at it."

Bolen grew up in Cleveland, Tenn., near Chattanooga. "I've followed softball since I was very young. Yes, Stan Harvey played there, and another fella named Ron Patterson. They were both great left-handed hitters. I started playing in Chattanooga for Burnette & Associates back in 1977. I'd been playing the game since I was 14. No sir, I never, was involved in sports in high school. Never played any baseball there. I guess I matured late. Right now, I feel like I can play softball 24 hours a day, but I've got a family—wife and two kids—and this traveling around gets real old. I've got another year left on my contract with Steele's, and after that's up, I'll take another look. I guess you could say Softball is sort of in second place in my life now."

Rick Weiterman, 28, is a Steele's anomaly, a singles hitter on a team of big hoppers. On the Alabama and Georgia tour, he had 23 straight hits—that's straight hits, not hits in 23 straight games—and only the last one was a home run. As he rounded the bases in, for him, an unfamiliar trot, Weiterman heard Neale cry out, "Oh, you've added a new dimension to your game," and somebody else shouted, "The wind must be blowing out awful hard." At 6'2", 225 pounds, Weiterman is, by Steele's standards, a little guy. But what genuinely sets him apart from his teammates is that he is a pitcher. Pitchers by slo-pitch standards, and especially by Steele's standards, are victims. "We are at the mercy of the hitters," says Weiterman. "I've been put on my back by line drives and hit in the shins. I've been lucky never to have been hit in the face or you-know-where."

A slo-pitch Softball pitcher stands only 46 feet from home plate, and with a brute on the order of an Elliott or a Fuhrman, that's just 46 feet from decapitation. A slo-pitch pitcher never steps forward delivering the ball; he unloads his lobs quickly, then scurries backward to get out of harm's way. His pitches must always have a "hump" in them—from 3 to 10 feet in elevation in the USSSA and from 6 to 12 feet in the ASA. Weiterman likes the bloopier pitches permitted by the ASA, but he enjoys the greater freedom the USSSA gives beleaguered chuckers. In USSSA games, a pitcher can indulge in the most outrageous shenanigans as long as he keeps one foot on the rubber when he releases the ball. Before he throws, the pitcher is permitted to taunt the hitter, wave his arms at him or. at the risk of life and limb, even run at him. Weiterman has thrown a behind-the-back pitch. And another Super-level pitcher, Bob Loria of Glass Wholesalers of Hammond, Ind., has performed somersaults before releasing the ball. In a tournament in Milwaukee, Wis., with Elliott at bat, Loria's entire team did somersaults before the pitch. Talk about your topsy-turvy games.

Weiterman thinks of himself as just another victim. "I can throw a knuckler, and if the wind is blowing out I can throw a good breaking curve," he says. "But you can't win. You just gotta keep standing in there and put it right down the pipe."

The interviewer from WTOC-TV in Savannah smiles hopefully up at Ken Loeri, the 6'3", 235-pound Steele's outfielder. Loeri is smiling, too, although he hasn't been in such a good mood lately. Last season his girlfriend unceremoniously dumped him. Since then, as everyone who has spent time with him knows, Loeri has been down in the dumps. Any mishap, on or off the field, seemed to call this amatory disaster to mind. "My girl left me, and now I can't hit the ball out.... My girl left me, and now this damn faucet won't work...." Although he's built like an NFLtight end, the loss of a loved one seems to have diminished him. Lovelorn Loeri he's called.

But before the camera he appears restored, for he is an unabashed Steele's promoter. A warehouseman for the company, he is also a talented illustrator who will soon be designing logos for the company's new tote bags and T-shirts. The TV interviewer wants to know how many runs Steele's will score against the local team from Thompson's Sporting Goods. "Oh," says Loeri, toying with some figures, "about 40." The television man smiles. "Four? Will that be enough?" "No," says Loeri, "I said, '40.' " The interviewer's smile shrivels. He cannot comprehend 40 runs in a game, so he tries another approach. "All ballplayers have goals," he says. "Tell me. Ken, what are yours for this season?" Loeri does not hesitate. "My goals for this season are to hit over 300 home runs and to bat .700." End of interview.

It is raining hard at six o'clock as the Steele's vans pull into Savanah's Eisenhower Softball Complex. Spectators and players alike wade ankle deep in mud outside the four diamonds and gather under the overhang of the unpainted brown shack which houses the concession stand. Park employees work—fruitlessly, it seems—to sweep and rake the infields clear of the ocherous pools that have formed on the base paths. Fuhrman, huddled in the snappy orange Steele's warmup jacket, checks the action outside the concession booth. "That one could play on my all-star team," he says as a leggy brunette wades past. "They say beer goes with softball. I say women go with it. Well, maybe women and beer."

There is a game already being played on the adjoining diamond, and the rain slackens a little. The infield has been transformed from a lake to a swamp, so the decision is made to play, if for no other reason than to appease the sizable crowd that has assembled to see if Steele's is for real.

It takes an inning to find out, for in Steele's half of the first, the unimaginable occurs—no runs. And in their half, the boys from Thompson's score eight. Could Steele's be in trouble? Not on your life. In the second, Virkus, Wright, Macenko and Fuhrman all hit homers that bounce off cars parked well beyond the fence. Bull's thunderous grunt as he hits his a mile is in itself enough to silence the opposition. Steele's hits 14 homers in the game and, ho hum, wins easily, 33-13. Now they will play a second game against Thompson's.

About the time the nightcap starts, the game on the adjoining diamond reaches the sixth inning. Watching it proves a revelation. The players—representinglocal teams from Stroh's and the Pony Express, according to their jerseys—are of normal size, and they're wearing motley uniforms and a wide assortment of caps. The game they're playing is not the same one Steele's plays. Ground balls are hit to the infield, for one thing. Steele's can go a whole game without giving opposing infielders an assist or the first baseman a putout. Ground balls are beneath them. You wonder why opposing teams even bother with infielders, since they are about as functional in a Steele's game as adenoids. In Columbus, Ga., the all-stars did, in fact, move their second baseman into the outfield. Actually, the best place for him would have been 30 feet beyond the outfield fence. But Stroh's and the Pony Express keep their infielders busy tracking down balls hit down the line and up the middle. They are also catching pop-ups. A Steele's pop-up is caught on the warning track.

What a strange game these lesser mortals play. While the ball is rocketing out of the lot with predictable regularity next door, Stroh's and the Pony Express are sliding into bases, beating out grounders and, yes, making errors. And their pitchers do not act as if their lives were in danger. By the end of their game, players on both sides are caked with mud. They laugh and embrace. They'll probably go out for a few beers and talk over the good plays and the bad. They look as if they have had a good time. There's probably not a hitter among them who has hit 10 homers all season.

Meanwhile, next door, the Bull or somebody cranks up and grunts and the ball goes out. Over and over and over again.

|